Groundwater is a crucial but often overlooked resource that sustains India’s agriculture, industries, and drinking water supply. Stored in underground aquifers—porous rock formations that hold water like a sponge—it serves as the lifeblood of the nation. The monsoon plays a key role in replenishing these aquifers, but the delicate balance between extraction and recharge is increasingly under threat.

India is the world’s largest extractor of groundwater, accounting for 25% of global usage. Millions rely on it for irrigation and daily needs, yet unsustainable withdrawal, pollution, and climate change have led to alarming depletion rates. Regions like Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan face severe groundwater stress due to over-extraction for farming. Managing this invisible yet vital resource is essential to ensuring long-term water security for future generations.

Status and Atlas

The National Groundwater Atlas provides a comprehensive assessment of groundwater availability across India, revealing stark regional disparities. While states like West Bengal and Bihar benefit from fertile alluvial aquifers and river-fed reserves, excessive withdrawal—especially in Punjab for water-intensive crops like rice—has led to significant depletion.

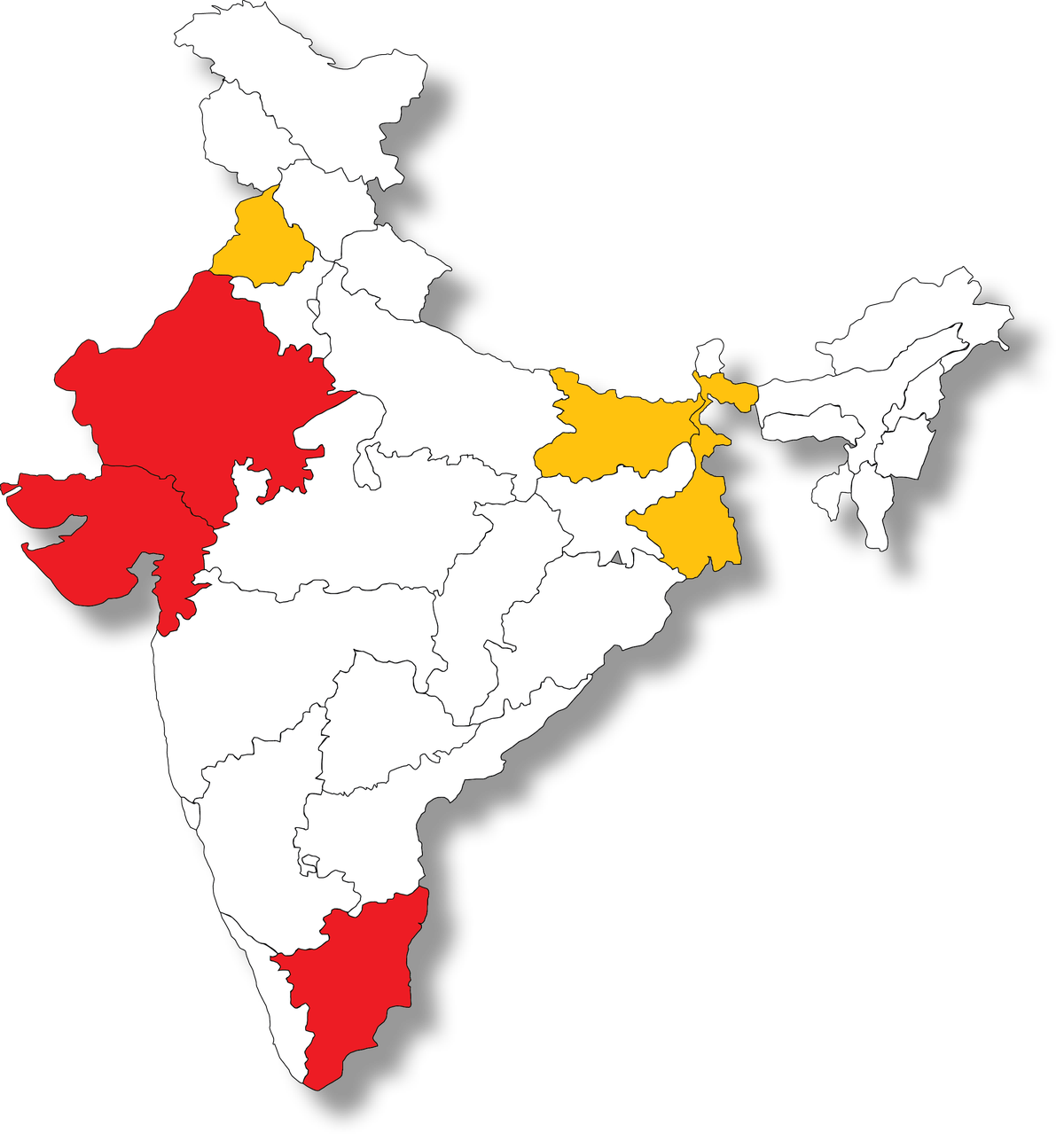

Groundwater availability in India: The map highlights regional disparities, with red-marked states (Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu) experiencing severe water stress due to low recharge rates and over-extraction, while yellow-marked states (Punjab, Bihar, and West Bengal) have better groundwater reserves but face depletion risks due to excessive withdrawal for agriculture.

Conversely, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu face severe water stress due to low rainfall, hard rock aquifers, and slow recharge rates. Gujarat presents a mixed picture, with some regions experiencing acute shortages while others benefit from river-fed reserves. The Atlas highlights these contrasts, offering crucial insights for policymakers to develop targeted groundwater management strategies. As over-extraction continues to outpace natural replenishment in many regions, sustainable conservation efforts are essential to ensure long-term groundwater security.

Key concepts:

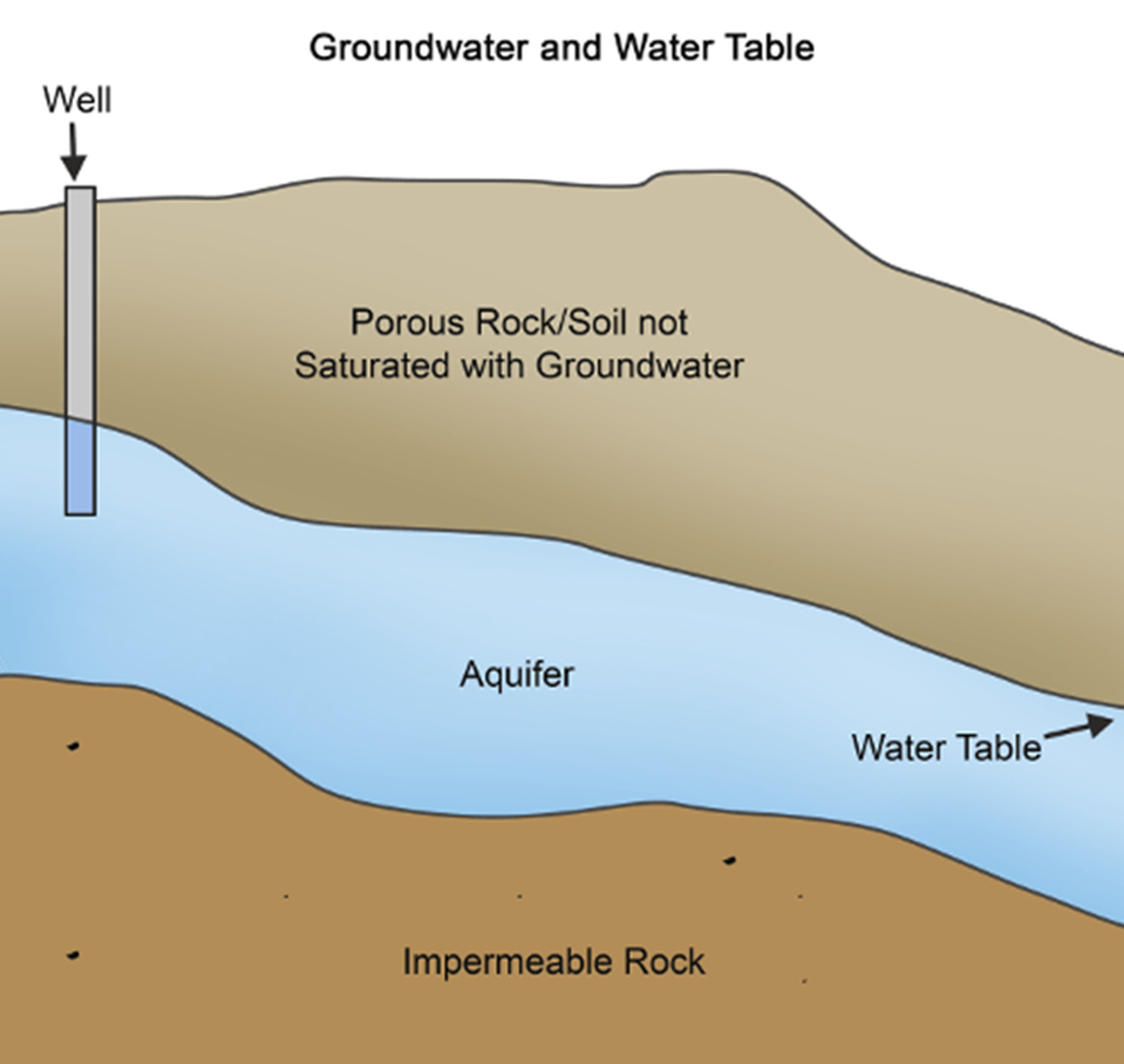

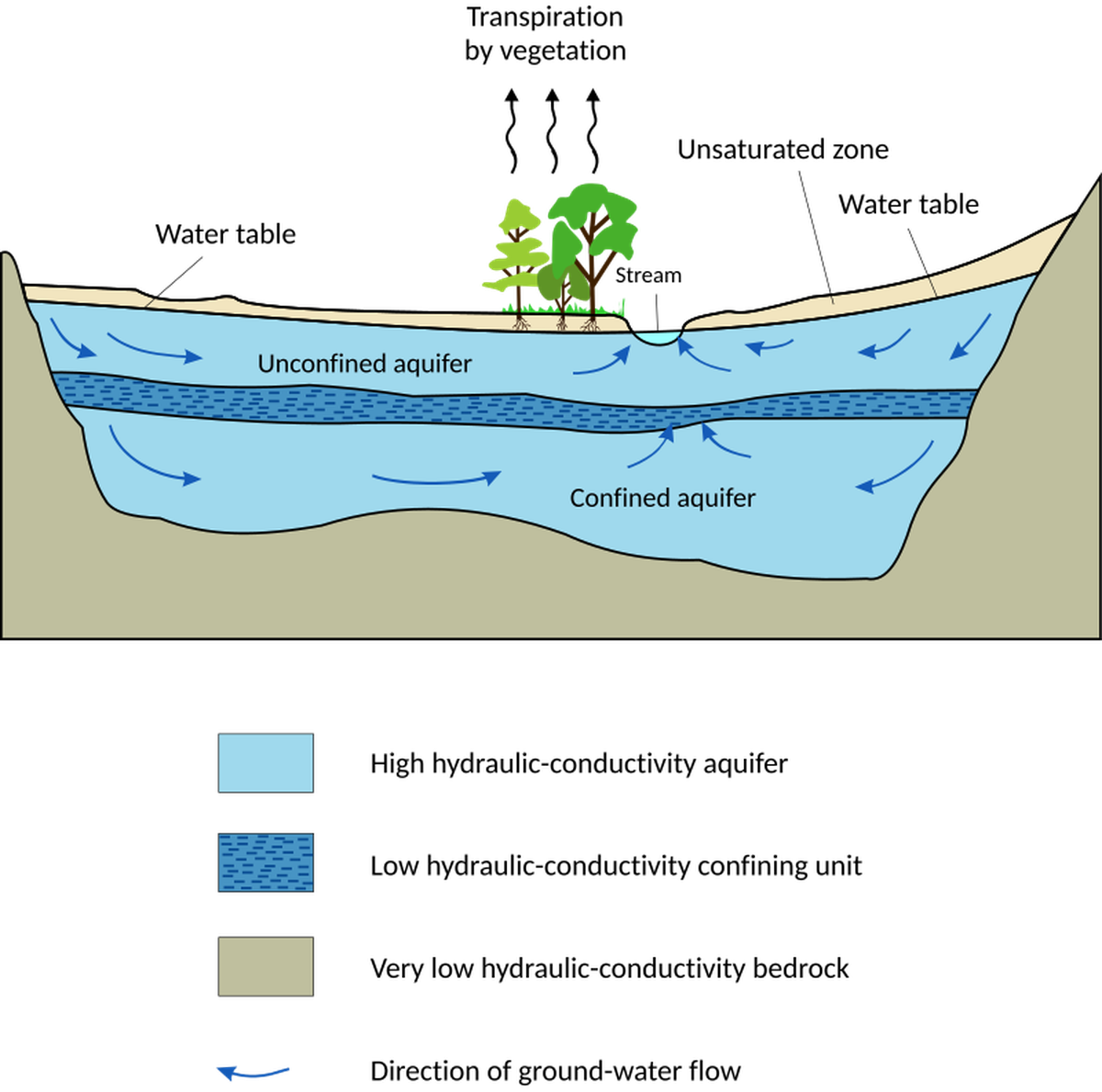

Aquifer: Underground rock/sediment layers that hold water.

Water Table: The upper level of groundwater in an aquifer.

Infiltration: Water entering the soil.

Percolation: Water moving downward through soil layers.

Treasure underneath

Groundwater is a crucial but often overlooked resource that sustains India’s agriculture, industries, and drinking water supply. Stored in underground aquifers—porous rock formations that hold water like a sponge—it serves as the lifeblood of the nation. The monsoon plays a key role in replenishing these aquifers, but the delicate balance between extraction and recharge is increasingly under threat.

A well at a farmer’s field near Humnabad Industrial Area filled with chemically contaminated groundwater.

| Photo Credit:

KUMAR BURADIKATTI

Threats

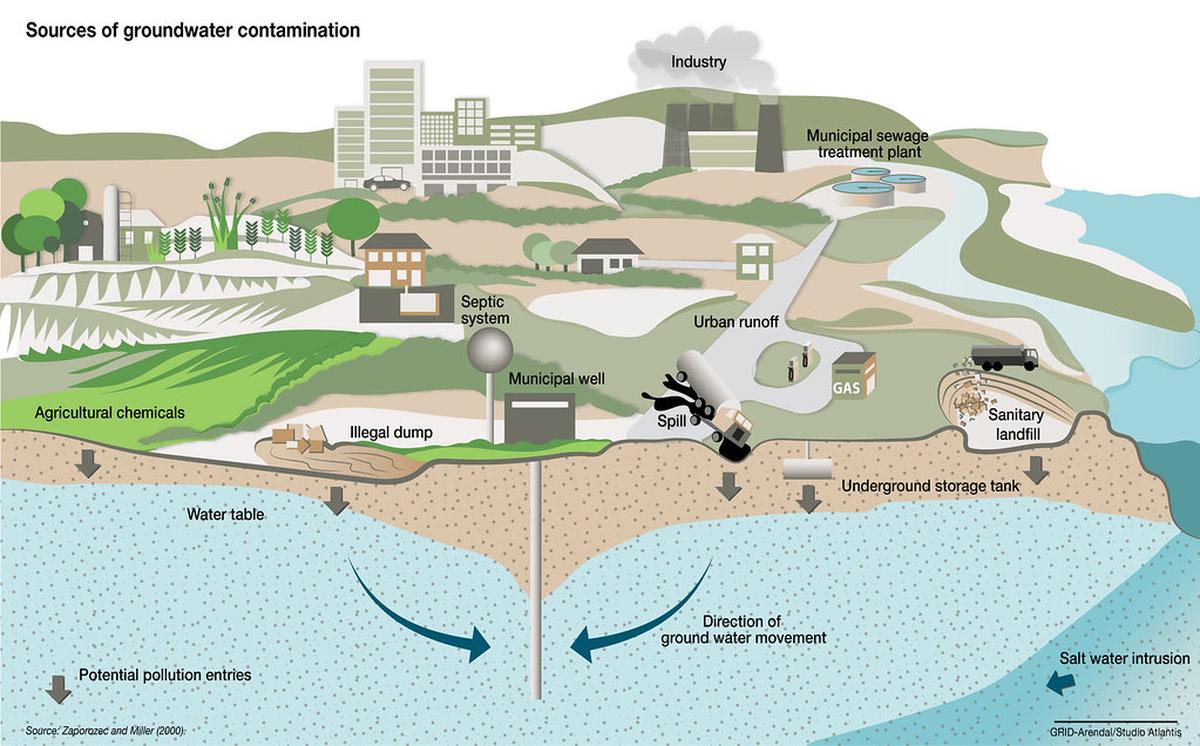

India’s groundwater is under increasing pressure due to over-extraction, contamination, and climate change, making sustainable management crucial for long-term water security.

Over-extraction: Excessive groundwater withdrawal for irrigation, industries, and urban consumption is rapidly depleting aquifers, especially in Punjab, Haryana, and Tamil Nadu. The unchecked use of borewells is pushing water tables to dangerously low levels.

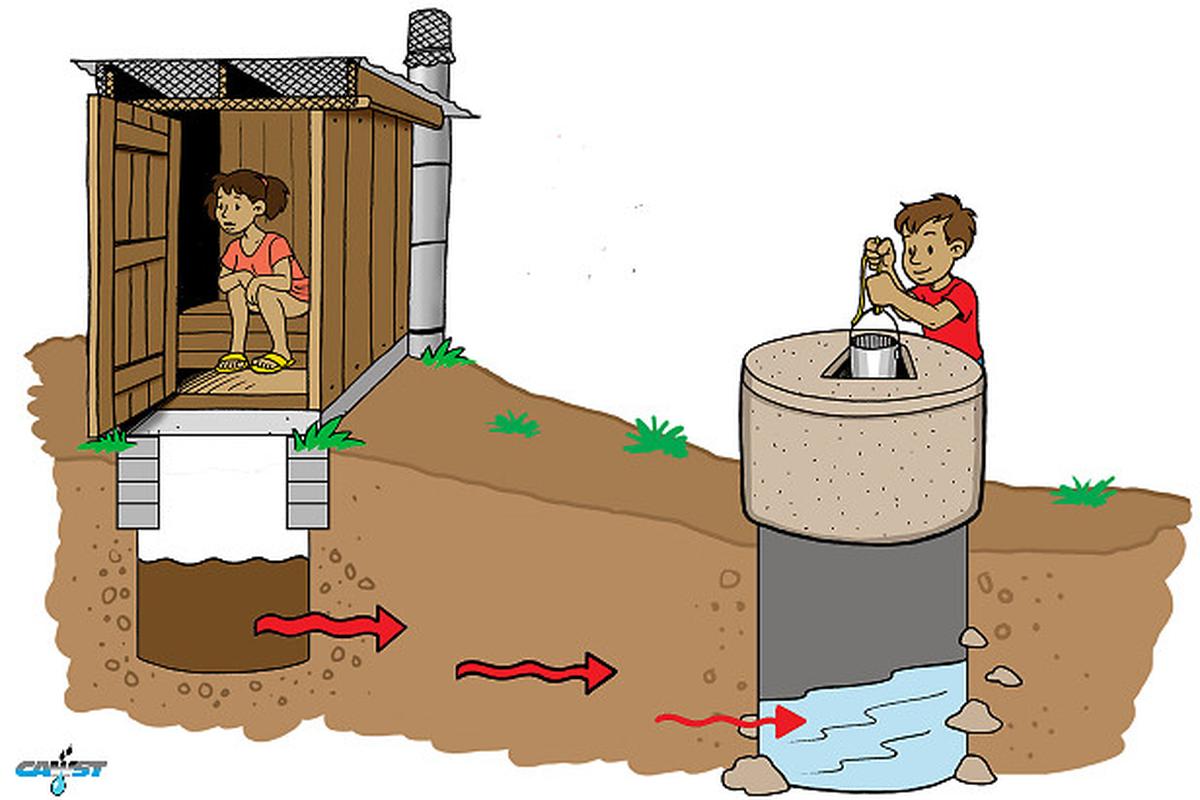

Salinity and contamination: Natural and human-induced pollution is rendering groundwater unsafe for drinking and agriculture. West Bengal and Bihar face high arsenic contamination, while Rajasthan struggles with fluoride contamination, posing severe health risks.

Climate change impact: Unpredictable monsoons, prolonged droughts, and rising temperatures are reducing groundwater recharge rates. Regions like Gujarat and Maharashtra are particularly vulnerable, with erratic rainfall worsening the crisis.

Groundwater contamination

Urban groundwater crisis

Cities like Delhi, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad face severe depletion due to unregulated borewell drilling and rapid urbanization.

Bengaluru water crisis (2024): Bengaluru suddenly became the centre of national attention as the city’s acute water shortage made headlines. Borewells ran dry, lakes shrank due to over-extraction and erratic rainfall, and residents in many areas were left scrambling for expensive private water tankers. The crisis sparked widespread discussions on social media and in policy circles, with experts calling for urgent action. Industries and IT hubs faced disruptions, forcing businesses to rethink their water dependency. The situation underscored the urgent need for rainwater harvesting, stricter groundwater regulations, and sustainable urban planning to prevent future crises.

Residents collect free water from a tanker amid water crisis, in Bengaluru.

| Photo Credit:

SHAILENDRA BHOJAK

Chennai’s Water Crisis (2019): Showcased the dangers of over-extraction, prompting greater focus on rainwater harvesting and artificial recharge.

The first special ‘water’ train with 2.5 million litres of water from Jolarpet to Chennai arrived at Villivakkam to help the city tide over the severe water shortage. The Tamil Nadu Government requested the Southern Railway to transport water from Jolarpettai to Villivakkam to supply 10 million litres per day of drinking water to the city.

How is groundwater recharged?

Groundwater recharging is a process of refilling underground water reserves (aquifers) through natural and artificial means.

Natural recharge

-

Precipitation: Rain and snowmelt infiltrate the soil and percolate down into aquifers.

-

Surface water: Rivers, lakes, and wetlands contribute to recharge as water seeps into underground layers.

-

Interflow & baseflow: Some water moves laterally through soil layers before reaching deeper aquifers, maintaining river flow in dry seasons.

-

Factors affecting recharge: Soil type (permeable vs. clayey), vegetation (roots create infiltration pathways), topography (gentle slopes retain water), and climate (rainfall patterns).

Artificial recharge

Humans actively assist groundwater recharge through methods like:

-

Check dams & percolation ponds: These slow down water flow, allowing more time for seepage.

-

Recharge wells: Specially designed wells directly inject water into aquifers.

-

Rainwater harvesting: Collecting and storing rainwater in tanks or directing it into the ground through recharge pits.

-

Canal irrigation: Water from canals seeps underground, replenishing local water tables.

-

Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR): In cities like Chennai, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra, treated water or excess monsoon runoff is injected into aquifers for later use.

-

Floodwater management: In flood-prone states like Bihar, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh, excess river water from the Ganga and Brahmaputra is diverted into recharge structures such as artificial wetlands and retention basins.

Traditional water conservation systems:

Baolis (Stepwells): Used in Rajasthan and Gujarat to collect and store rainwater.

Eri System (Tamil Nadu): Ancient tanks built for water conservation and groundwater recharge, still in use today.

Zabo System (Nagaland): Indigenous water harvesting method that integrates agriculture and livestock farming.

Why is groundwater recharge important?

-

Maintains water availability during droughts

-

Prevents over-extraction and depletion of aquifers

-

Supports rivers, lakes, and wetlands by maintaining underground flow

-

Reduces soil erosion and land subsidence

Revival of wells in Rajasthan: A success story

In Rajasthan’s Alwar district, the revival of traditional johads (check dams) has transformed barren lands into fertile fields. Led by community efforts, these structures helped recharge groundwater, restoring dried-up wells and ensuring water security. This success story has inspired similar conservation projects across India’s water-stressed regions.

Published – March 22, 2025 11:00 am IST